Fifteen species of calcareous sponges (phylym Porifera, class Calcarea) are known from the Disko Bay area, and nine of these have their type locality here, which means that this was the area they were fist described from. During this fieldtrip we wanted to collect calcareous sponges from Disko to get material that can be used for genetic studies to investigate the relationships between the populations in Disko Bay and populations of what is believed to be the same species in other localities.

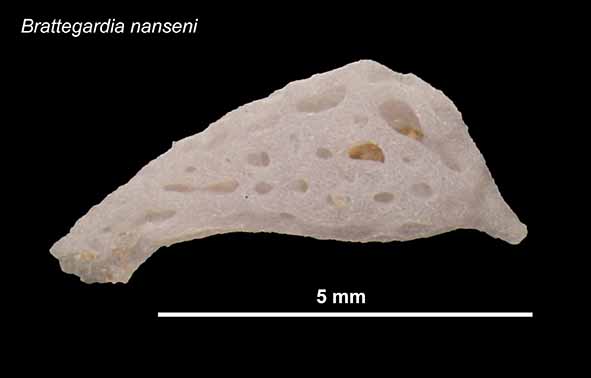

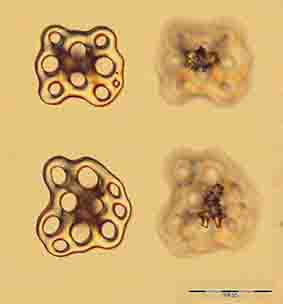

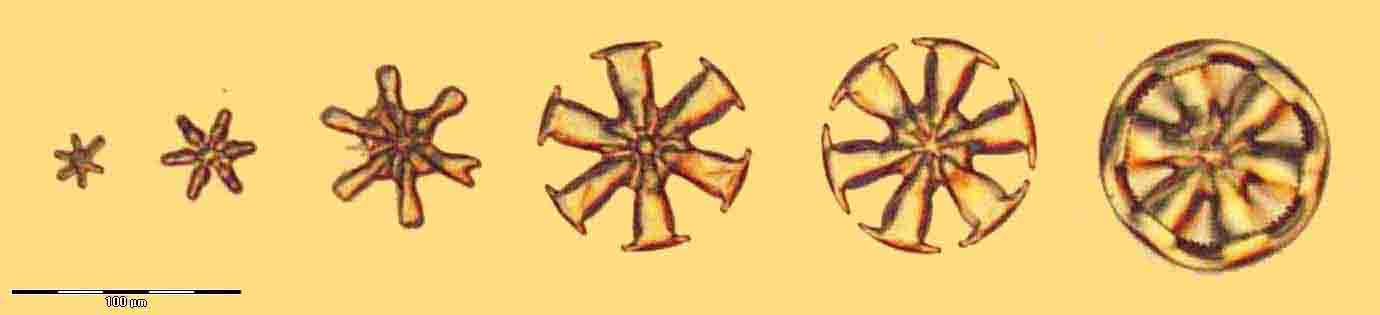

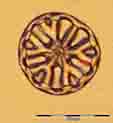

Identifying calcareous sponges is not a straightforward business; first of all they are very small (most < 1 cm), and secondly they do not have any obvious external characters like bright colours, legs or even a head. In stead they have spicules. Spicules are small needle-like structures that function as the skeleton of the sponges, and in calcareous sponges they are made out of calcium carbonate. The shape of the spicules is an important character to identify sponges, in addition to the morphology of the sponge body and the arrangement of different types of cells. To look at the spicules of the sponges we need to clean the spicules from tissue and mount them on microscope slides. We cut out a piece of the sponge and add household bleach, which is left to work for 30 minutes, followed by three rounds of cleaning with distilled water, each taking 30 minutes. To make a permanent slide that we can look at again and again we use an imbedding medium that takes about 24 hours to dry sufficiently, so the time between we find a sponge specimen until we can identify it can be quite long.

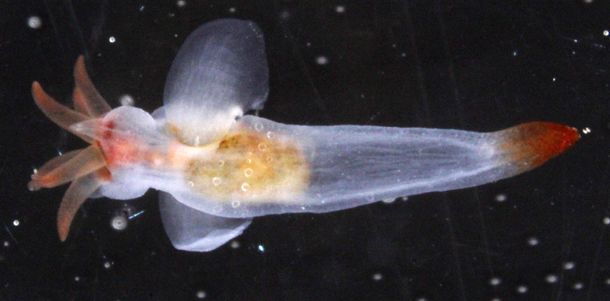

We have had quite good sampling success so far, with over 50 specimens of calcareous sponges, and a few sponges of other classes. Most of the specimens were found sitting inside globular aggregations of Lithothamnion, a red algae (described in an earlier blogpost). Getting the sponges out from the Lithothamnion was tricky, both because they are very small and hard to spot, and because they were sitting quite far inside the globules, probably to get shelter. We also got many specimens from a triangular dredge sample that was sieved through a 1mm sieve. This is also where we found our largest specimen so far on this course! A beautiful Leucandra penicillata with a length of a whopping 5 cm! The calcareous sponges we have identified belong to at least eight different species, but the material has to be examined by experts to be certain of the identification.

Not all the samples we collect are equally interesting, but ones in a blue moon something special comes along. Yesterday, while sorting through the material from the dredge, we realized that we had just found the remnants of our good friend Spongebob Squarepants! It was a sad day indeed as we sieved out our global mascot from the murky waters. A memorial was thrown in his honour with the Greenlandic flag on half a pole. But life goes on and so does the search for new exciting sponges in different parts of the world!

By Henning and Mari (University of Bergen).

Featured image: Variety of calcareous sponges from Disko