Do you remember that feeling of dread before you must present in class about a topic you didn’t really study for? Your mind racing, trying to scramble a coherent story to tell the sea of eyes fixed expressionless on you and your powerpoint? We believe we all have at least one memory of this from our days in college.

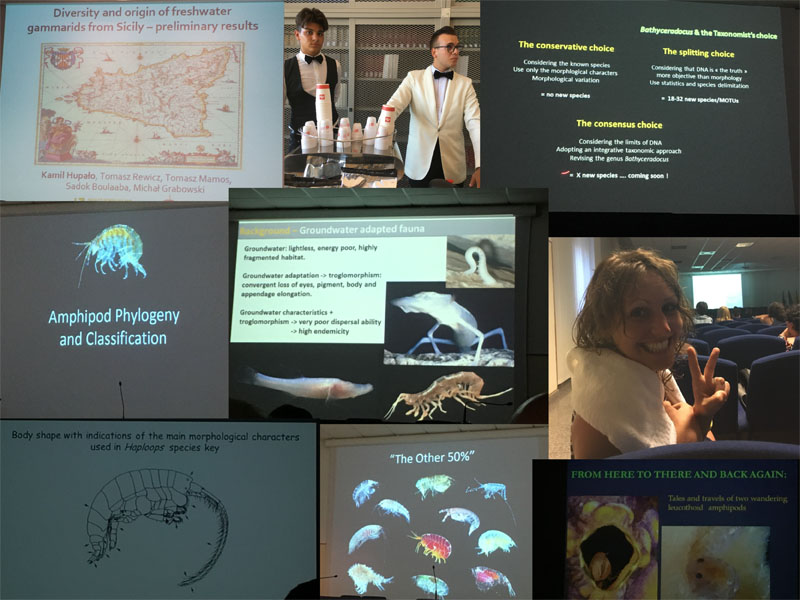

That was a similar feeling to what we felt on November 28th, 2022, when we had just landed in Trondheim and were on our way to the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) for this year’s ForBio Meeting, a 3-day gauntlet where we will present the Master’s projects we’re currently working on. Except this time, we weren’t presenting in a small classroom full of uninterested teenagers thinking about tik tok dances, but in an auditorium full of fellow researchers who work on your same field, and who will probably have extremely difficult questions at the end of your talk. Being the first time we present in an environment like this, one can’t help but imagine all the worst outcomes

And so we’re sitting there, watching the hours and the talks go by, thinking to ourselves “I should/shouldn’t try that for my talk!”. At lunch, all we think about is our talks. When we’re doing some light sightseeing in Trondheim, all we think about is our talks. We’re laying in our beds the night before, and all we think about is our talks. “How will I make my topic sound as professional and knowledgeable as I want to?”, we think to ourselves.

The day arrives, and again the dread starts setting in, right until the moment they call each of our names. At our every turn, we walk down the steps, grab the microphone, and start talking. Except for some reason, this time it feels like we’re in control. The words flow effortlessly; we even crack a joke or two, and the audience laughs. There’s no stumbling around the words like those college days.

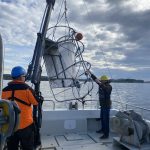

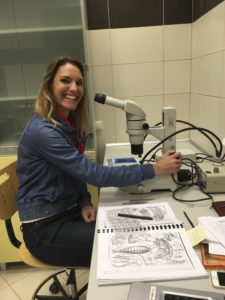

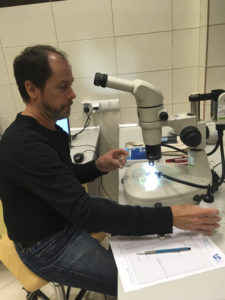

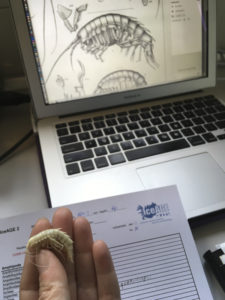

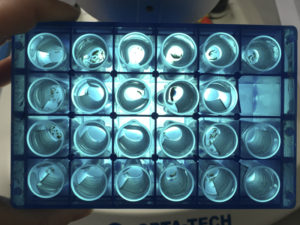

Because this time, we’re not the average seat-warming student. This time, we’re the ones that have spent cold and raining hours on a research vessel or diving to get our samples; we’re the ones who have spent hours working together with our supervisors, reading and learning about our topics; we’re the ones who have spent hours looking down a microscope trying to identify our organisms. This time, we’re the ones who know what we’re talking about, and the audience is there to learn from us.

After each of our talks, we give our acknowledgements, and everyone claps. The questions thrown at you are answered effortlessly, and the moment is finished with a thumbs up to our supervisors, returning to our seats smiling.

- Pedro presents…

- Håvard presents…

- Ana presents…

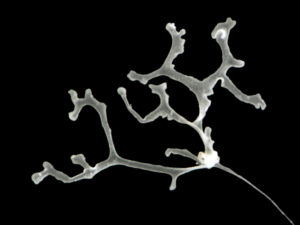

The most exciting part for us was showing to experts what we do with our favorite invertebrates: Hydrozoans. These organisms are an inconspicuous class in the phylum Cnidaria that most people ignore. Our job was not only to present what we do with them, but to show what they are, what they do, how fascinating they can be and why they are important. And we think that we did a good job.

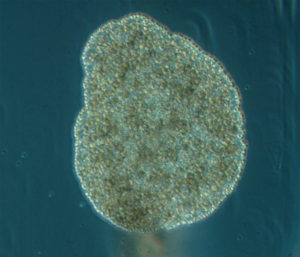

- Clytia hemisphaerica. Photo: Ana González

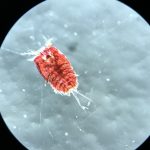

- A Mnemiopsis with a Hyperoche inside. Photo: J.J. Soto-Angel

Now we’re finally free to enjoy the world famous Trondheim bike lift (and the Nidaros Cathedral too), closing the night with burgers, beer and friends.

Everything has been great on this trip and we will always remember the advice from other professionals; how different or similar the work of each one is; and the feeling that you are part of a group of specialists who are excited to share their knowledge with others. But, above all, we have learned why these conferences are important: Knowing what other researchers are doing gives us the chance to collaborate together and help each other, because working as a team is how science moves forward.

Pedro, Ana & Håvard