Sea slugs and San Francisco

I am three months into the second year of my masters in marine biology, and was lucky enough to start off this semester with a three week trip to San Francisco in order to collect material for my project.

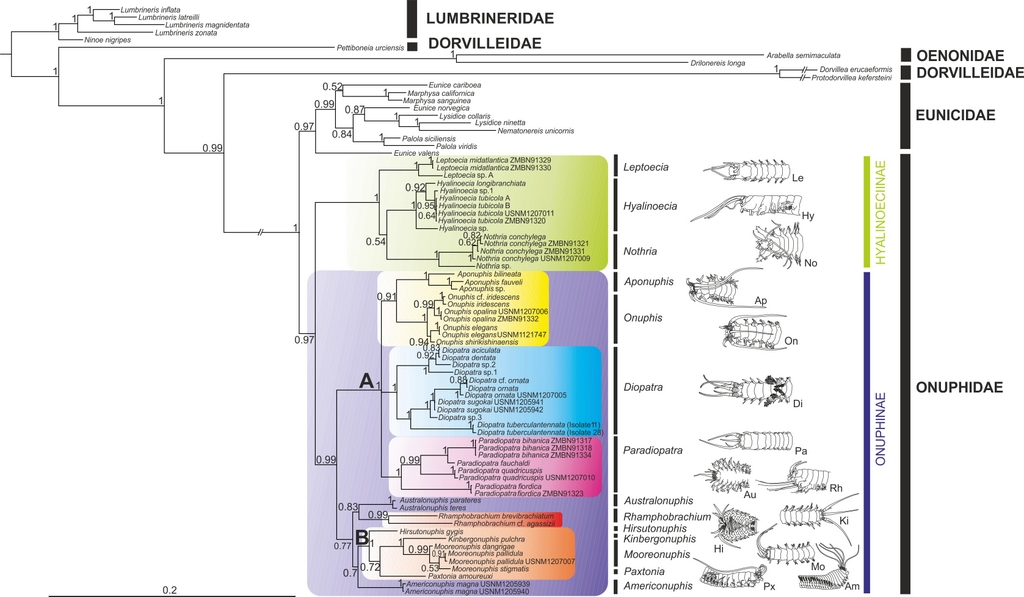

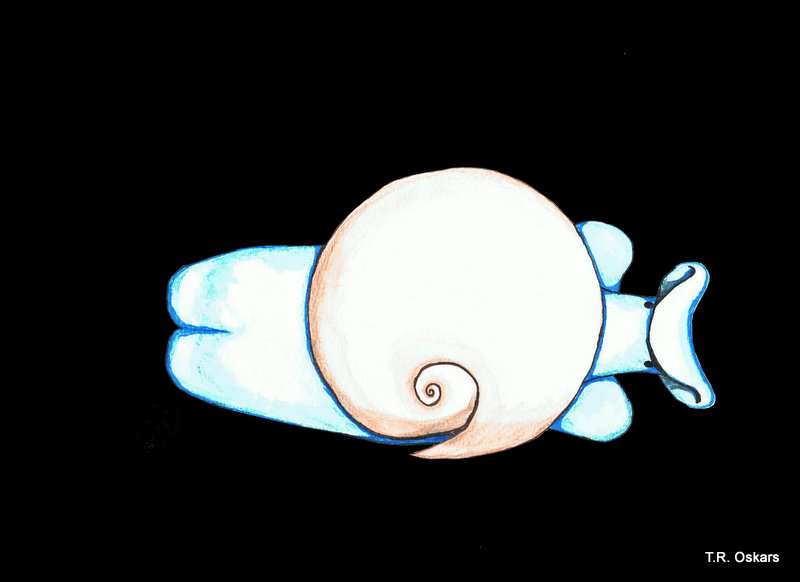

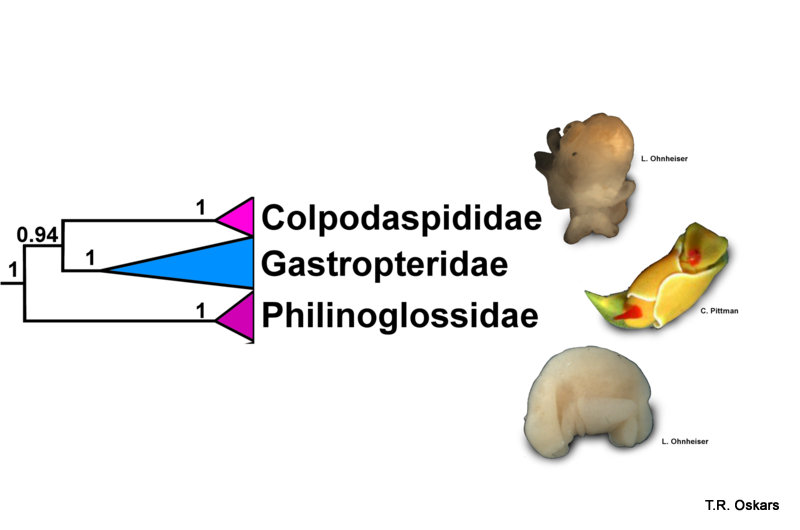

I am writing my master thesis for the University museum of Bergen on the phylogenetic systematics and evolution of a small marine gastropod.

The title of my project is “Patterns of speciation in the Indo-West Pacific, with a systematic review of the genus Phanerophthalmus (Cephalaspidea, Haminoeidae)”.

I will be using an integrative taxonomic approach combining fine-scale anatomical dissections and molecular phylogenetics to revise the taxonomy and be able to better understand the relationships of the species. The group is restricted to the shallow waters of the Indo-West Pacific and may therefore be used as a good model to study speciation and the historical biogeography of other organisms in this region.

In order to obtain specimens for this project loans have been made from various museums and academic institutions around the world. In total I have 60 specimens on loan from these various institutions, however they still only represent part of the diversity of the genus with limited geographical coverage. The California Academy of Sciences (CAS) in San Francisco holds the largest collection of sea slugs in the World, including specimens of the genus Phanerophthalmus, with over 100 specimens. So, it was arranged for me to visit this large collection and assess what was important for my project. Travelling to CAS also meant I was able to work alongside Dr. Terry Gosliner, a leading expert in the field of malacology.

So, on January 16th I got on a 10 hour flight to San Francisco. I stayed at a guest house in the Richmond district of San Francisco, about 40 min walk or 30 min bus from CAS.

Waking up on Sunday morning I was a bit jetlagged, but super excited to be in San Francisco. As it was Martin Luther King Jr. day tomorrow (Monday), I had two days to recover from the flight and adjust to the time difference (9 hours behind Bergen!).

I decided to go and explore the city so I took a bus to downtown San Francisco and went to Fisherman’s Wharf, to Pier 39 where the Aquarium of the bay is and also the California sea lions.

On Monday I went to see where I was going to be spending the next three weeks: at the California Academy of Sciences. Situated in Golden Gate park, the surroundings were beautiful.

After visiting the grounds of CAS I wandered over to the Golden Gate Bridge. There was rain in the air and the fog was coming down but the view of the bridge was spectacular.

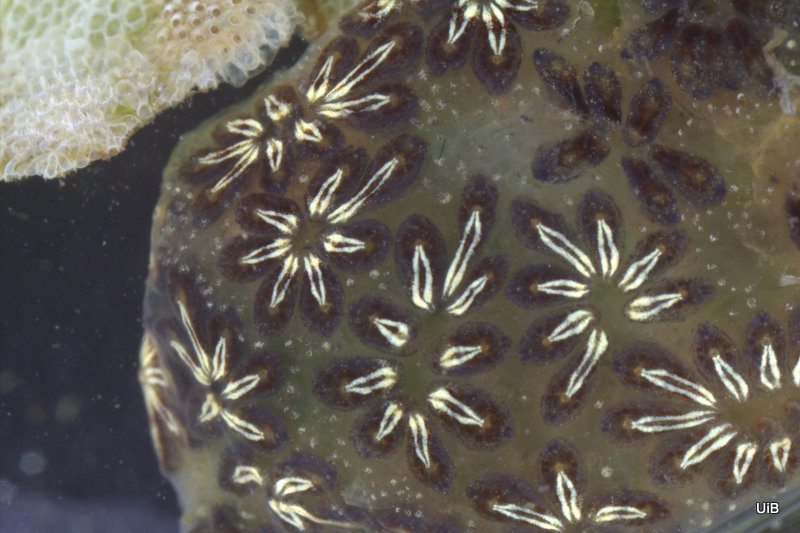

Tuesday morning I arrived at CAS eager to dive into the collections. Terry met me at the staff entrance and after a chat and a coffee we got to work. The CAS database contained more than 100 specimens of Phanerophthalmus. The first few days were spent examining labels and matching live photos with specimens. The amount of material was a bit overwhelming and even though I would have liked to look at it all, this would not be possible during my short three week visit. So with guidance from my supervisor, Manuel Malaquias, I was able to focus on the most important specimens. As I am looking at the phylogeny of Phanerophthalmus it is important for me to have specimens which I can extract DNA from. It is also useful to know what these animals looked like live in order to maybe use the external morphology as a character for determining species.

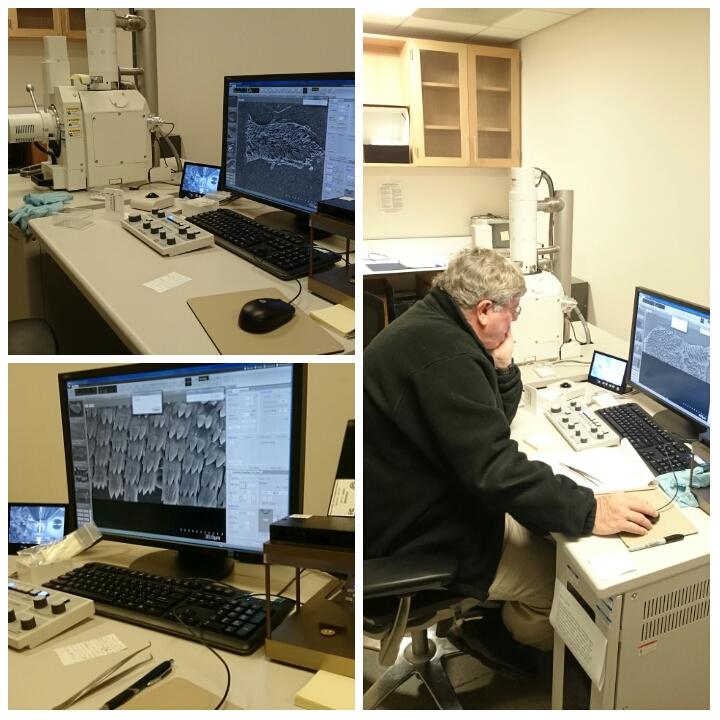

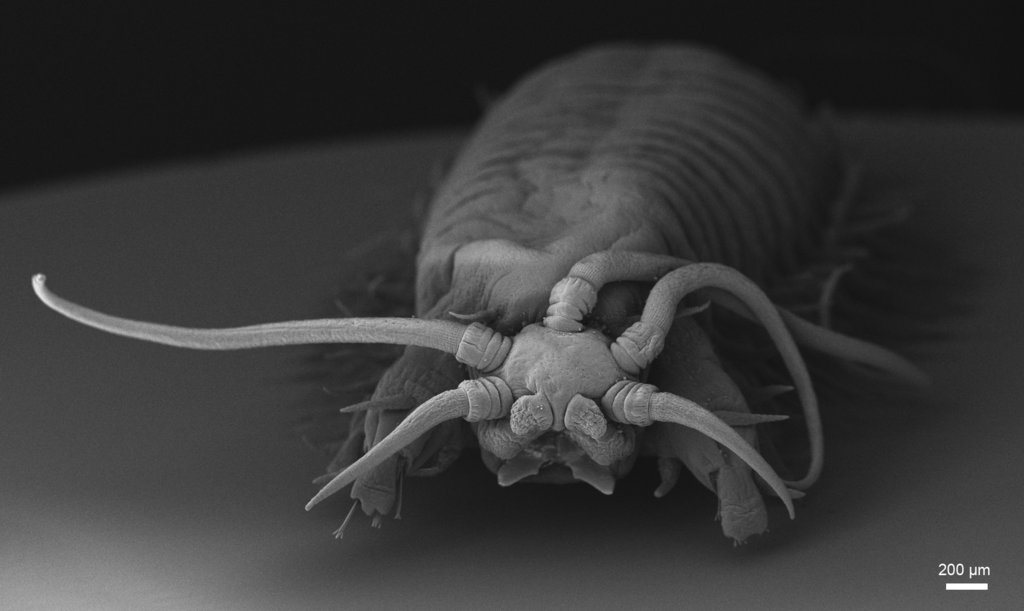

The three weeks flew by so quickly. I spent my days with the collections, dissecting specimens and also got the opportunity to try the academy’s brand new scanning electron microscope. Terry was an amazing host and kept me busy. A huge thank you to him for dedicating so much time towards helping me out. Also, a huge thank you to everyone else at the academy for being so nice and welcoming. After my three weeks at CAS I had a few days to be a tourist in the city. My last weekend in the city happened to be Super Bowl 50 weekend and the city was buzzing with people and events. All in all I had a great visit, and now I have lots of material to carry on working with back in Bergen.

The collections (top), my dissection station (bottom left) and the male reproductive of Phanerophthalmus

-Jenni