Colobocephalus costellatus repainted from M. Sars (T.R. Oskars)

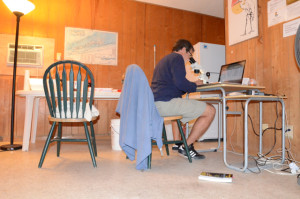

When researching small, obscure sea slugs you are bound to run into surprises. Partly because it often takes a long time between discovery and identification, and also because a lot of the really interesting stuff is first revealed when new methods become widely available.

In 2011 a team of researchers from the Invertebrates collection were sampling specimens in Aurlandsfjorden for the Invertebrate collections and range data for the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre (Artsdatabanken). Among other interesting critters they found a 2 mm long white blob. While not initially impressive this small blob turned out to be the enigmatic cephalaspidean sea slug Colobocephalus costellatus (Cephalaspidea: Heterobranchia) described by Michael Sars from Drøbak in 1870. At the time of its re-discovery it was thought that this species, which is unique for Norway, had not been seen or collected since M. Sars first laid hands on it 145 years ago (more (in Norwegian) here). However, you continuously discover more information in the course of scientific work. During their work on the enigmatic slug Lena Ohnheiser and Manuel Malaquias found in the literature that the species had in fact been discovered a couple of times since 1870, first by Georg Ossian Sars in Haugesund some years after his father, and more recently by Tore Høisæter of Bio UIB in Korsfjorden outside Bergen.

Still, no in-depth analyses have been done on this species since M. Sars until Nils Hjalmar Odhner of the Swedish Natural History Museum drew the animal from the side showing some of the organs of the mantle cavity.

Most authors have had real difficulties to place this slug within the cephalaspids, and M. Sars even thought is possible that the slug might not be an opisthobranch. Some placed it within Diaphanidae based only on the globular shell, a family that has been poorly defined and often used as a “dump taxon” for species that hare hard to place. Yet others thought it might even be the same as the equally enigmatic Colpodaspis pusilla, which has been suggested to be a philinid sea slug (flat slugs digging around in mud and sand).

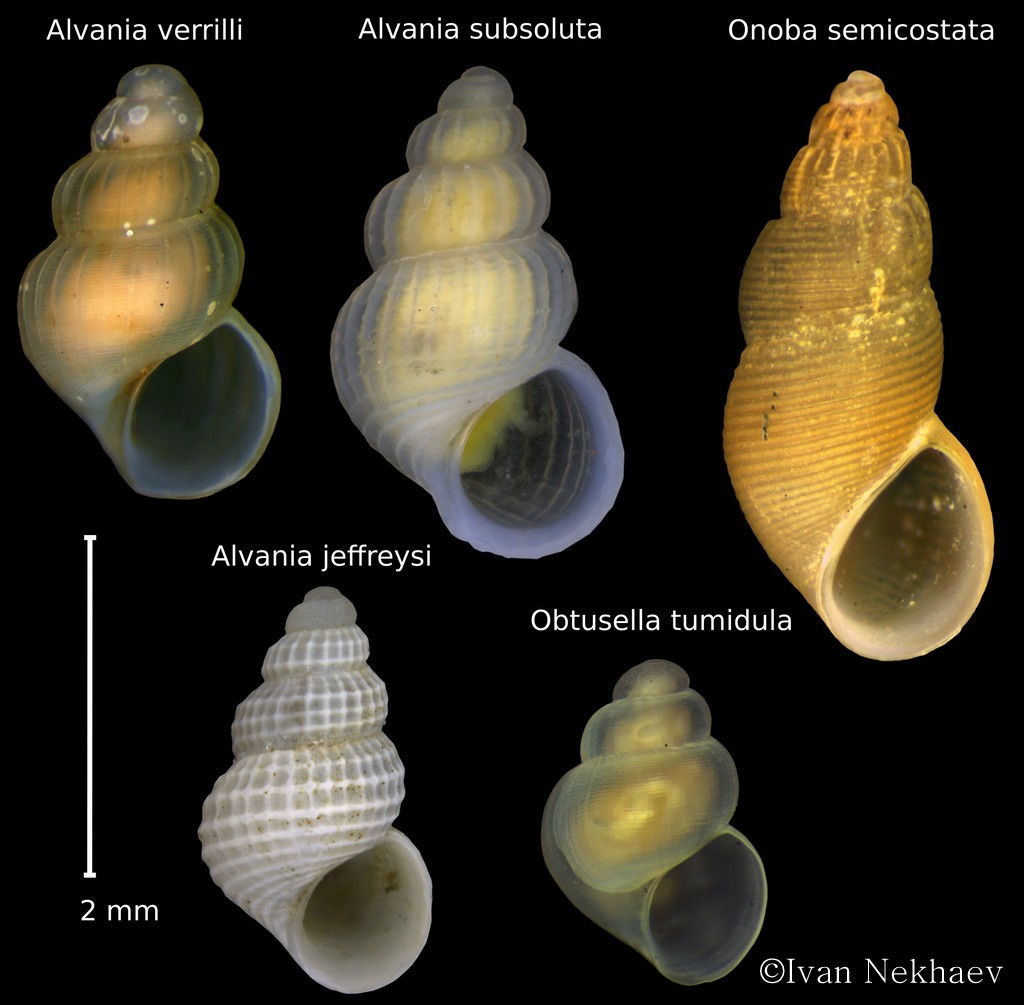

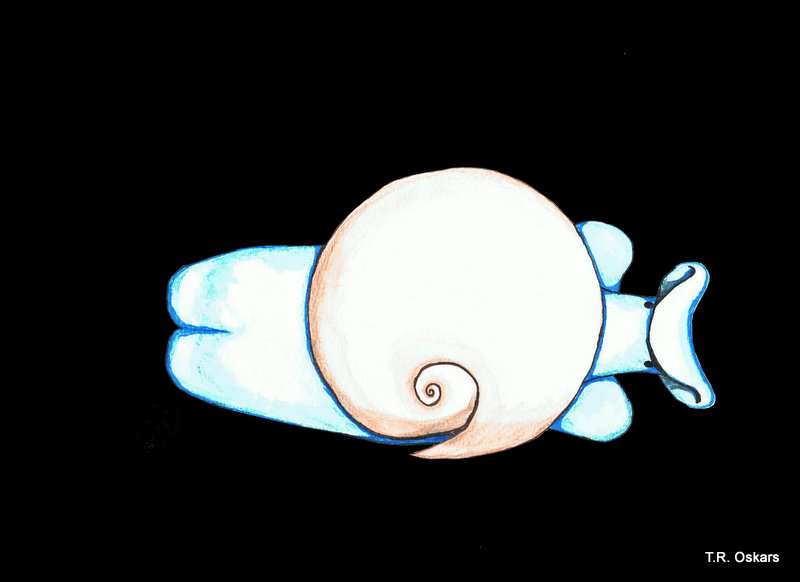

What was unique about the most recent find was that this was the first time it was collected alive and photographed with high magnification. The material was also so fresh that Lena and Manuel could dissect the animal and study its internal organs. In their 2014 paper “The family Diaphanidae (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Cephalaspidea) in Europe, with a redescription of the enigmatic species Colobocephalus costellatus M. Sars, 1870” they tried to resolve the relationships between these globe shelled slugs. What they found was that Diaphanidae was likely not a real grouping of species, containing at least three distinct groups, where one group was Colobocephalus and Colpodaspis, which were closely related to each other, but also quite distinct.

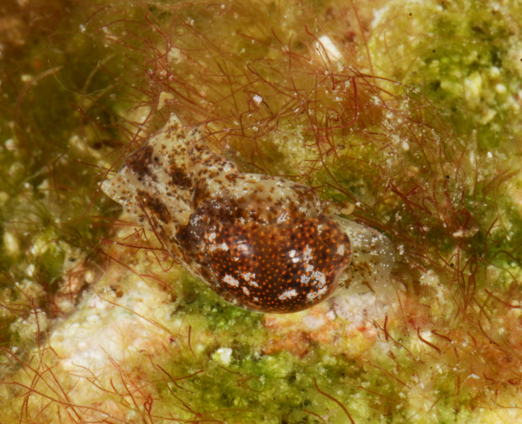

Colobocephalus costellatus M. Sars, 1870. Photo: Lena Ohnheiser, CC-BY-SA. Also featured on http://www.artsdatabanken.no/File/1292

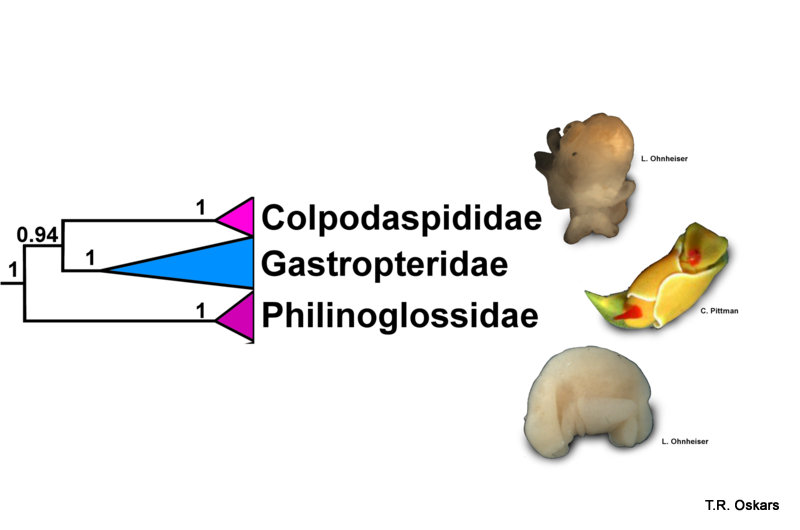

Another new development with the sampling in Aurlandsfjorden was that the slugs were preserved in alcohol rather than formalin. Formalin is good for preserving the morphology of animals, but it destroys DNA. On the other hand, alcohol is perfect for preserving DNA. This lead to C. costellatus to be included in a 2015 DNA based phylogenetic analysis of cephalaspidean sea slugs.

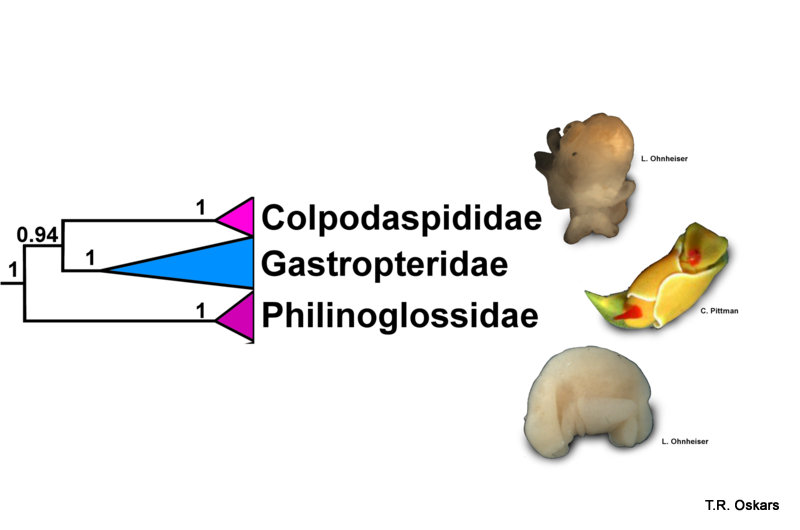

Modified Tree from Oskars et al. (2015)

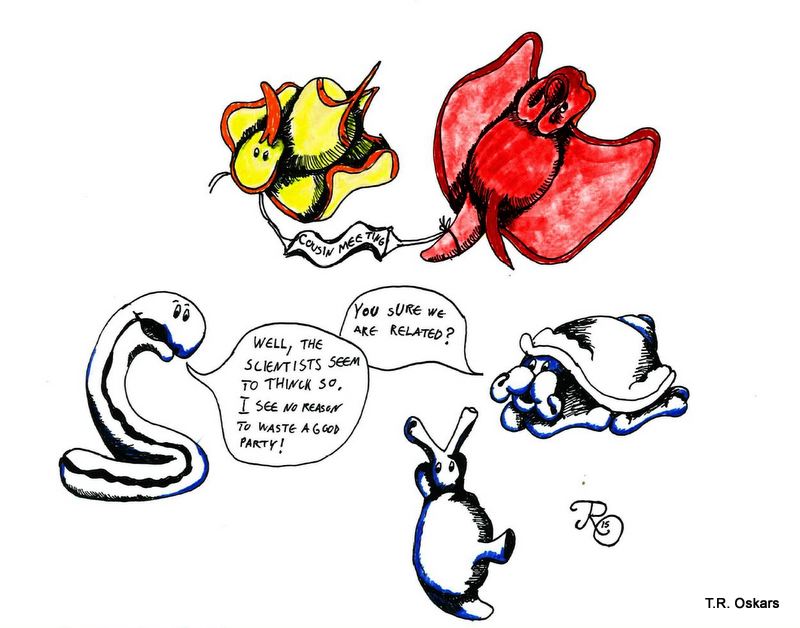

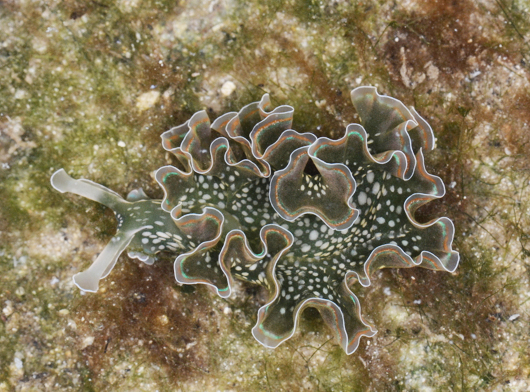

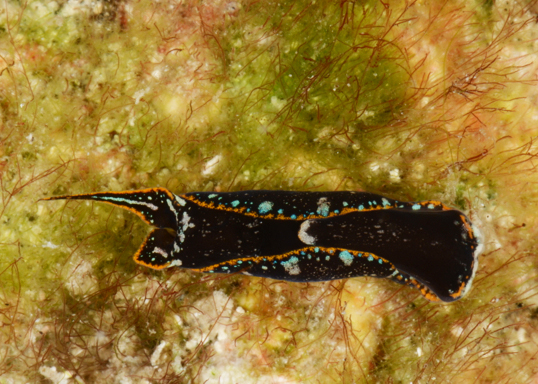

This resulted in that the slug was found to be indeed an Opisthobranchia, and as Lena and Manuel thought, Colobocephalus and Colpodaspis were placed in their own family, Colpodaspididae. Whereas the traditional “Diaphanidae” was split apart. Even weirder was the sea slugs that were shown to be the closest relatives of Colpodaspididae, which were neither the philinids or the diaphanids. The closest relatives turned out to be slugs that are equally as weird and unique as Colpodaspididae, namely the swimming and brightly colored Gastropteridae (sometimes called Flapping dingbats) and the Philinoglossidae, which are tiny wormlike slugs that live in between sand grains.

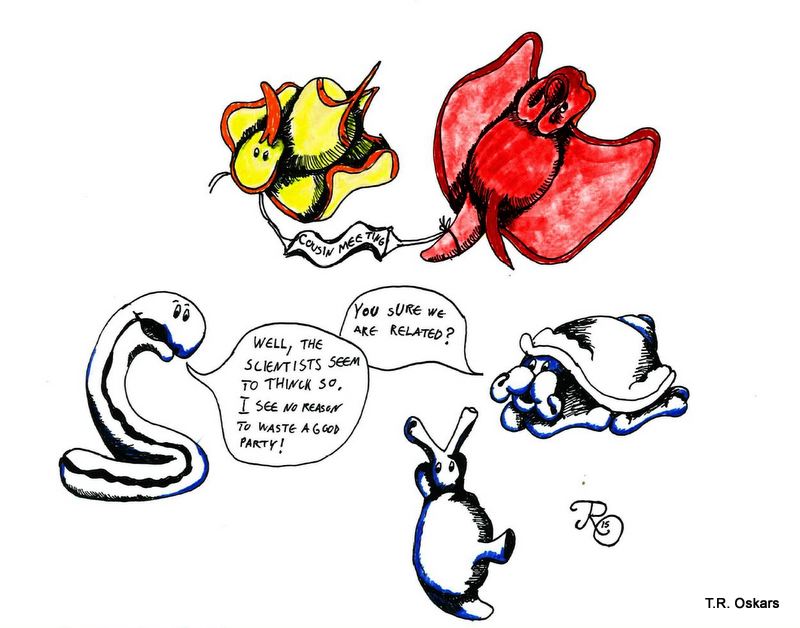

*Cousin Meeting*

– “You sure we are related?”

– “Well, the scientists seem to think so. I see no reason to waste a good party!”

So it took 145 years from its discovery before Colobocephalus became properly studied and its family ties revealed, but it is still mysterious as we do not know much about their ecology or diet.

Suggested reading:

Colobocephalus costellatus: http://www.biodiversity.no/Pages/149747

Colpodaspis pusilla: http://www.biodiversity.no/Pages/149766

Philinoglossa helgolandica: http://www.biodiversity.no/Pages/149915

Høisæter, T. (2009). Distribution of marine, benthic, shell bearing gastropods along the Norwegian coast. Fauna norvegica, 28.

Gosliner, T. M. (1989). Revision of the Gastropteridae (Opisthobranchia: Cephalaspidea) with descriptions of a new genus and six new species. The Veliger, 32(4), 333-381.

Odhner, N.H. (1939) Opisthobranchiate Mollusca from the western and northern coasts of Norway. Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskabs Skrifter, 1939, 1–92.

Ohnheiser, L. T., & Malaquias, M. A. E. (2014). The family Diaphanidae (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Cephalaspidea) in Europe, with a redescription of the enigmatic species Colobocephalus costellatus M. Sars, 1870. Zootaxa, 3774(6), 501-522.

Oskars, T. R., Bouchet, P., & Malaquias, M. A. E. (2015). A new phylogeny of the Cephalaspidea (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia) based on expanded taxon sampling and gene markers. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 89, 130-150.

Sars, M. (1870) Bidrag til Kundskab om Christianiafjordens fauna. II. Nyt Magazin for Naturvidenkaberne, 172–225.

-Trond